Scroll down: all shorts, short stories, articles, essays are original, protected by intellectual property laws...

Following: The Blacklist/ HItler's Schnozzle/ Poverty/ Kingdom of Tootsie (Romanoff Goats)/ Toobie or Not Toobie/ Westside Plumber's Association/ Captain Chris/ Autumn/ China's Trade Attack/ Hubert/ Dangerfield's Drum/ Three Travelers/ The Neighborhood/ Poodle's Cardroom/ Port Moresby at Three a.m. / Mondavi's Ride Home/ The Desert/ The Prisoner (creative nonfiction)/ The Bad Guys/ The Alley/ North Butte/ The Old Dog on the Hill/ The Invisible War (a.k.a.The Forgotten War)/ The Lost Man and the Dog/ The Sochi Olympics/ Ms. McTavish/ The Taverna/ I'm Not A Real Mawtch-Ho Man/ Moon Over Reno (Chapter One)/ The Playground/ America (an essay on America)/ The Carbuncle/ Absolute Chaos: The Pascal Leemur Caper/ Ready or Not Here Comes Eva/ American Hockey Players/ St. Nick/ Wee Men/ Two Strong Men/ Caterina Zutzcu and the Three-Legged Dog/ The Porta-Potty Peeper/ The Only Freakin Normal Guy in Town/ Hoity Toity (Chapter 2, Otis Moon)/ Beirut/ The Birth of Her Caitness/ Jackalopes and Househusbands/ The Three Almost Wise Men/ Charlie Chan Movie Review/ The Garden of the Beasts Book Review/ Carl of Hollywood/ Travel the World For National Geographic Book Review/ Electronic Friggin Banshees (creative nonfiction)/ Lucky Louie/ Jimmy Cagney and Father O'Hara: pictures of two friends..

If you like any of the following work, stories, download any, and wish to donate $ to the continued life of this site, its author and its technical and photography support team, please send check to 200 P Street/ A-32, Sacramento, California 95814, payable to Kevin O'Kendley. I'll pay the taxes...

Please see Buy a T-shirt section for original t-shirts, slogans, cartoons.

If your nonprofit organization has a blurb in the following section and you wish it removed for any reason you can reach me at the site's contact section or at ksokendley@outlook.com and I will remove the ad.

I worked as a cartoonist and columnist in the 20th Century, my work appeared in publications from Maine to California.

My last published short story appeared in the Honest Ulsterman, Northern Ireland (the summer of 2018) but is not in this list. Though, not always identified, some of the following shorts have been published in the U.S. and the U.K.

I'm relatively old: I was married for 18 years; my ex-wife and I have two children that grew up in New England, my daughter is a college student and my son is in the Navy....

Photo by Caitlin Maeve O'Kendley (my daughter

is a college student studying media and journalism)

is a college student studying media and journalism)

The Blacklist

By Kevin O’Kendley

Otto found himself on a super-secret international blacklist of toilet paper buyers/users for undisclosed secret reasons that may have been about his penchant for wearing a London Fog raincoat and Stetson fedora in Midwest sporting supply outlets specializing in croquet equipment and related acrobatics, or because he was an Independent. After he found himself being followed around by nondescript men also wearing raincoats and fedoras he started wearing Bermuda shorts. That’s when this happened: no matter where he attempted to buy a roll of toilet paper the vendor was either out of stock or didn’t know what it was.

After a couple of weeks without toilet paper Otto started to drag his, uh, you know what. After months of dragging his "you know what" and he still couldn’t break the bathroom tissue blacklist -- not in Rio, Bonn, Toledo, Darwin, Mumbai, or Bangor -- he grew desperate. Obviously, given the situation, he had to adapt (and quickly).

So, he tried newspapers: the New York Times, the Klondike Sun, the Fresno Bee…

This, of course, is where things got interesting:

While newspapers aren’t as form-fitting-cuddly as Charmin, Otto did notice that they had printed words on them. This discovery led to another discovery, and another; in fact, there were stories, headlines, columns, cartoons, exposes, all kinds of information, and other cool stuff in the freakin newspapers.

So, Otto started reading the papers before he used them (sometimes, after he used them, he complained that the newspapers were full of sh-t).

No matter what armchair philosophers say: that which doesn’t kill you doesn’t necessarily make you stronger -- it can make you crazy, catatonic, or married -- but as an avid newspaper reader Otto became more erudite, wiser -- learned -- and a better haggler when buying fish (wrapped in newspaper) than he had ever been before.

Huh?

Despite this, the recent Supreme Court ruling that struck down a “person’s legitimate right to fair and equitable access to purchase toilet paper from any vendor or source that sells or provides toilet paper to anyone, unless the seller doesn’t freaking feel like it for any arbitrary reason of prejudice, hatred, or speculative slander,” was a real bummer. I mean, hell, once you’re on The Toilet Paper Blacklist you can pretty much kiss your ass goodbye. -end-

Hitler's Schnozzle

by Kevin O'Kendley

Hitler had a full mustache, which he whittled away, first on one side of the nose then the other trying to create precise order, or exact Nazi uniformity of lip hair on each side of said nose (schnozzle in Yiddish). He repeatedly failed at regimented order until he had just a tiny little maniacal mustache left, but equal in length on each side from the center of his nose (schnozz in Brooklynese). Electing to maintain this atrocious order instead of growing a better, luxuriant, and more evolved mustache Hitler re-trimmed said affectation and social blunder in the same manner ever afterwards, calling it perfect. Of course, even though all of his Nazi sycophants told him he had a Homeric mustache you’ll notice not one of them copied his mustache, not even Herman Goering and he wore jodhpurs and a man-bra.

Hitler used to wear a lot of Aran sweaters, too, from Aran Island off the coast of Ireland, because he thought the Irish couldn’t spell Aryan correctly (a real smart Irish businesswoman told him that). Though -- back in real life -- Iran (the actual country), meant even then as it does now: the place of the Aryans (in Persian).

So, Hitler didn’t know what the hell he was talking about when he claimed that the Teutonic/Germanic tribes of ancient lore were Aryan -- he even got the swastika backwards, except when he accidentally wore his swastika-stamped underwear inside out, which Eva Braun mused was "quite often, the silly little Nazi turnip."

When Hitler finally committed suicide he had given up completely on evening-up his mustache on each side of his nose (schnozzle in Yiddish) and was clean shaven. - end -

Poverty

By Kevin O’Kendley

Poverty can be both the inspiration

and ruination

of dreams

but the tipping point is at the heart of a nation. -end-

The Kingdom of Tootsie or

The Romanoff Goats

By Kevin O’Kendley

There’s a small, two-thousand-acre national monument called the Kingdom Of Tootsie on the borders of Nebraska and Wyoming up near South Dakota in the vast American Steppes. In the early years of the Great Depression the Kingdom was stashed away and became a kind of national secret.

Can you remember what a secret was?

By 1931, as man became more urbane and technology more invasive secrets became more accessible to voyeurs, eavesdroppers, tattletales, etc., so some secrets were hidden within the context of popular songs.

For instance: Miles and Miles of Texas by Bob Wills had a secret line in the song that firmly suggested a fundamental truth about Texas that might have caused philosophical issues thereby trade indelicacies during the Depression between Texas and let’s say Rhode Island. It was this part: “Miles and Miles of Texas.” No one could sing a song about miles and miles of Rhode Island without it being a rather short song. In the Great Depression many song writers had to be discreet or face starvation, or at least use a nom de plume. The societal camouflaging of the Kingdom of Tootsie appeared within Al Jolson’s song Toot-Toot Tootsie Goodbye as secret/hieroglyphic-speak: “Toot-Toot Tootsie Goodbye.”

Why? One word: goats. Two words: Romanoff Goats. Two more words: Tootsie Rolls.

That’s why.

There were people that knew Tootsie was there but it was a complex social secret, and of course the goats weren’t quite right. According to Darwin they couldn’t exist -- but they did and that was a problem kind of like Shaquille O’Neal in a Mini-Cooper. Independently of each other the Mini is a grand creation and so is O’Neal but stick the Shaq in the Mini and -- well -- is Shaq too big or is the Mini too small?

Whatever your position in this debate you might be willing to concede that something could be askew --

Not unlike the Romanoff Goats: named after the Russian accidental-explorer James Romanoff.

Not long after the War of 1812, Captain Romanoff hiked inland from the Russian settlement of Fort Ross (California) searching for the Big Valley, or what is known today as the Sacramento Valley. He missed the glacier-scoured bottom-land but ended up in Southeast Oregon. Huh? Romanoff was confused (possibly the vodka), recalculated his position, but in re-configuring or “plotting” his course he forgot in which direction the sun rose and so set. Thinking it set in the east he struck east for the Pacific Ocean, only the Pacific was in the west unless you were in China. In fact, the sun still sets in the west and rises in the east, except during certain political debates where doubt, uncertainty, and a solid lack of information is the primary component of most argument.

Anyway: Captain James “The Great Navigator” Romanoff crossed northern Nevada, then Utah, and then Wyoming before he ran into the largest abandoned prairie dog colony in North America. By this time the exhausted Romanoff thought he had circumnavigated the earth or in fact had found the great land passage from America to Asia, which so many covered wagon manufacturers and oxen breeders and boot makers dreamed of.

What he saw astounded him:

Hundreds of goats with two short legs and two long legs tumbling, stumbling, falling, and crashing-into-each-other. Or, did the peculiar acrobats have two regular legs that just seemed longer because the other legs were so short? Whatever: the Russian was delighted, it was a little like his native St. Petersburg only without top hats and carriages yet somehow more romantic and “more precise in its natural anarchy.”

An elderly Lakota Sioux gentleman in traditional garb and wearing the whole feather headdress thing came over to him and said, “Cuppa tay? Two bob.”

“All I got iss rubles.”

“Blimey, I was kidding,” the American said, smiling at the Russian. “Incredible creatures, wot?”

“Yess -- My name iss James Romanoff,” the Russian said.

“My name is Tootsie.”

“What are those -- how you say -- uh, mole hills?”

The Lakota Sioux wise man smiled. “Prairie dog mounds, old chap. A prairie dog town.”

“Yess. Prairie dugs.”

“Good show,” Tootsie said. “Almost. It’s prairie dogs, though. D-o-g-s. Can you say dogs? C’mon. You can do it. Good boy.”

“Dugs?”

“Yes, well, you’re nearly there, sir.”

“Vaht iss wrong with goats?”

“By gadfrey sir they have two long legs and two short legs. They were bred for going in only one direction on the side of the steep Rocky Mountains.”

“Oh.”

Originally from the Flatiron section of the Rockies the mountain goats were indeed equipped with two short legs on the port side and two long legs on the starboard side so as to better travel on steep terrain. Of course, as Tootsie said they could only travel comfortably in one direction.

So it was bound to happen, sometime between 1640 and 1705 while changing directions in the middle of the night the goats tumbled down a steep ravine at about where Boulder, Colorado, is today (there’s a secret plaque in Toms Tavern commemorating this historical occurrence, ask the bartender and then tip heavily or you’ll never see it). The mountain goats followed their leader Hoses (in Pawnee: He Who Hoses Goats or just Hoses Anything) back up the mountain top. Only being long-legged on the one side and short on the other and of course walking over tumbled granite debris the goats fell down a lot, got confused, and headed off in the wrong direction following their leader (who by this time didn’t know where the hell he was going). As they did so they began to travel in ever larger half-moons, a phenomenon of their cockeyed gait, intersecting, waning and emerging, zig-zagging and whatnot, until they found the abandoned prairie “dug” colony on the border of Wyoming and Nebraska, or about two years (as a one-winged crow flies) after they left the Rockies.

Being a pragmatist Hoses told the other goats in braaas, shrugs, looks, stomping the hoof thing, etc.: “These hills are as good as we’re going to do so let’s just accept the situation and make the best of it.” But, even on the side of the steepest prairie dog mound the mountain goats didn’t really have their sea legs. They were cockeyed, lurching, and fell this way and that. Since traveling was now problematic and since the prairie dogs left behind so many spacious and interconnected homes the pragmatic goats moved in.

So, the mountain goats became the burrowing goats, thus becoming another group in a long conga line of Americans ready and willing to adapt to the problematic and to situations that just stink. Or, as Andrew Carnegie, the Scots-American steel magnate (not magnet), might have said, “Remove the cap of limitations, expand the definitions, create and survive, and maybe you’ll make a little dough while you’re at it.”

Also, he may have said this next thing: “Ye cahn hov rrrrr wives but ye cahnt hov rrrrrr freedom,” which was immortalized in the movies Braveheart and at the end of Stepford Wives.

Over time the Lakota people grew to admire the burrowing goats.

Yes, the Sioux thought the tumbling, tipping, ungainly goats were living editorial cartoons on the nature of man, a testament to civilization -- no matter whose -- and many Americans came from miles around to watch the goats live their lives in boundless optimism and zestful physical heroics, without actually getting anywhere. Heck, even staggering from one burrow to the next was an accomplishment that the Lakota cheered and believed in. Watching a burrowing goat go in one hole only to pop up from another hole fifty feet away brought even greater cheers from the appreciative spectators. Some of the unpracticed gymnastics was breathtaking and long before the Olympics resumed in 1896. All of it, of course, was a lesson in humility and guts and a no-quit testament to goats.

The old Prairie Dog colony evolved in grasslands eons old, a boundless splendor that someone could see, if someone looked, for days on end in any direction. What someone couldn’t see was the natural springs, sorghum, Indian wheat, burrowing goat cheese, and other goodies, a mixture of which became a staple that the goats both consumed, plastered tunnel walls with, and used for medicine, which allowed the community to flourish, while giving back and establishing this circle of life in the old prairie dog colony.

Chief Tootsie, of the Hammersmith Clan, took Captain Romanoff to a large mound on the edge of the former prairie dog town. They stopped at a wide hole. The elderly American got down on his knees reached into the hole, scooped up a handful of the brown morass, and said, “You should bloody well try this, mate.”

At first the Russian was reluctant, given the circumstances, but after just a taste of the mysterious stuff he was hooked. The goo was excellent. What it needed though, was some tweaking and some baking -- some experimenting, you know.

Over the next few days the American and the Russian would mosey over to Tootsie’s Hole, grab some goo, and take it back to Romanoff’s fire pit where they experimented in baking the stuff. Eventually they had a very yummy treat. All the Sioux loved the stuff, even the ornery Crazy Bag Lady and her husband One Eyebrow. The fussy Blackfeet “just adored” the stuff, and so did a visiting Methodist couple from Wisconsin that had a background in advertising and communications.

The partners began to call the finished delicacy “Tootsie’s Hole,” shortened from the stuff from Tootsie’s Hole. But even to Romanoff (who was learning the King’s English from Tootsie) this didn’t sound right. Besides, the baked goo was brown so “one should be careful in what one called this stuff.” Since they cut it in squares, rolled it up like sod, over time the name finally graduated to Tootsie Rolls.

The American staple caught on first out on the frontier but quickly moved Back East. The concoction became a huge success, and virtually “overnight,” too, especially in Wisconsin. It was about this time that the burrowing goats finally began to be called Romanoff Goats (if you were wondering), after Captain Romanoff, the first white man or Russian the goats had ever seen.

Since the goats couldn’t travel, and the two partners didn’t want to go anywhere, traders, business people, consumers, had to come to the place of burrowing goats and the two chutzpah bakers. Another story that swept the dire places of the world was that there was now a place in America just for goats, lost goats, scapegoats, or any kind of goat.

After the free market forces of supply and demand were underway the Tootsie Roll took off and the semi-predictable occurred, which included but was not limited to the expansion of production facilities, introduction of hotels and restaurants, roads, plumbed bathrooms, churches, an army post, and a house of ill repute, all of which grew up around the old prairie dog colony or what some were even then calling the Kingdom of Tootsie. All manner of goats began to show up, too, especially of the human variety. Not unlike Australia or Boston (former British penal colonies) it wasn’t long before the losers were running things.

The symbiotic and natural relationship between the burrowing goats and the human goats grew over time. A culture of cosmic interaction, natural partnership, and the pursuit of the common good evolved but not like a machete and a banana tree, or even a hammer and a nail, but more like sexual intercourse.

Just as it was true that many of the losers in the Old World were winners in the New World it was true that many who were losers everywhere else became winners in the Kingdom of Tootsie. Former slaves, dissidents, outcasts, black sheep, retired adventurers, recusants, iconoclasts, science fiction writers, left-handed plumbers, Tourette’s-Syndrome-inspired teachers, the Irish, etc. These and many other folks found a home of forbearance, tolerance, and forgiveness in the Kingdom of Tootsie.

At that time most everywhere, even if she were a librarian, a woman couldn’t own land: but she could in the Kingdom of Tootsie. By 1907 the Burrowing Goats gained the right to vote by presidential decree, signed into law by a real goat fan: Teddy Roosevelt. Though it was 1920 before women could vote throughout America, there was never a time that they couldn’t vote in Tootsie. Native Americans didn’t become legal voters until after World War II in the United States but they were voting their conscience in the Kingdom from the very beginning. Heck, the Kingdom of Tootsie became a refuge for all goats no matter the breed, tribe, color, sex, or social status.

If you were a goat or a loser (and even if you weren’t) you were welcome.

Brraaaaaa.

Eventually things got too big, the goat tunnels grew exponentially wider and deeper and more numerous, there were cave-ins, the “molehill” mounds were bigger and growing larger by the day without comprehensive environmental planning, the lay of the land became strangled with a self-devouring physical- and spiritual-sapping sprawl, the hub of the booming candy business grew too large for the tiny Kingdom of Tootsie. So the primary factory packed up and moved to Chicago because nothing is too big for The Windy City, man.

It was at about this time, too, that the Russian’s son and daughter, Ira and Mona (yes someone actually married the old goat), started Romanoff’s Restaurant in New York City, originally featuring the excellent candy from The Kingdom of Tootsie and another instant success, Great Plains Buffalo Chips.

In the early part of the Twentieth Century Teddy Roosevelt made the Kingdom of Tootsie a national monument by presidential decree. Once again he didn’t need Congress for anything. Man, did that get him in trouble. But, of course the flagrant story of presidential exuberance and many other Teddy tales are better told by David Brinkley in his book, The Wilderness Warrior.

After the Crash of Wall Street in 1929 America held on by a thread, gumption, and bold-faced derring-do. But, even then it was touch and go. The Great Depression was a financial catastrophe and a nearly bottomless social upheaval in the American landscape and not just a semi-sinkhole or tourist magnet (not magnate) on Highway 50 in central Nevada. However, in the beginning of the end of the beginning of the end of just a tad of the financial devastation inflicted by unbridled greed and unregulated banking, and a host of irresistible free-market destructive forces building steam for decades, were some goats and losers and a small, little, brown candy --

A candy that sold in Argentina, Finland, Spain, South Africa, China, France, Columbia, Delaware, Turkey, Greece, Kansas, both Lewistons, and Fresno. A commodity that grew in spiraling demand: a tasty treat that sold out the world over. A money-maker that brought cold hard cash to America when she needed it the most. An anchor to stop the nation’s financial slide into the deeper waters of financial mayhem. A warm and fuzzy idea that fostered other inventive ideas, and even more after that: like Tootsie-in-a-blanket, Tootsie Surprise, even a movie in the 1980s (Tootsie) starring Dustin Hoffman. Tootsie Rolls were a food stuff that helped finance the Lend Lease Program sending war materiel to the Soviet Union and Great Britain in order to fight the Third Reich --

An American candy:

Dun-da-dunta-da-da-dun!

Which is why the Nazis attempted to steal the secret recipe and destroy The Kingdom of Tootsie.

This is how it happened:

Not having thermal imaging radar or satellite surveillance back then to investigate or peep inside of people’s homes or the hundreds of miles of burrowing goat tunnels, the Nazis, who were disguised as cowboys and their horses, had to stop and ask directions. Just outside the primary goat tunnel, the Holland Tunnel, the sinister saboteurs asked a young goat by the name of Adolfo where the secret recipe vault was. The raiding party reportedly said that they worked for the Post Office and had a package for one of the secret recipe guards -- “Joe-uh-Clem-er-Dave-id-ah-Mike.”

Now, normally, a very accepting,trusting and kind Romanoff Goat, Adolfo became alarmed by the “cowboys.” Why? Because they had their pants tucked into their boots (and they didn’t do that at the time in Nebraska or Wyoming or The Dakotas except in the movies or in extreme wetland croquet), and “the so-called cowboys” were wearing Bavarian suspenders with little dancing frauleins (single women) on them and most cowboys at that time wore suspenders with somber colors or with little wagons or horseshoes on them. Also, some of the horses were muttering in German. And of course there was this: one horse said to another horse in good Spanish but with a pronounced Alsatian accent, “Tuve strudels demasiados y necesitoir al bano.” Which meant: “I had too many strudels and I have to use the bathroom.”

See: what the Nazis didn’t know was that Adolfo had been well educated by the nuns and knew this: Spanish horses don’t eat strudels.

The smart little goat gave the raiders the wrong address and written directions that led through a series of winding tunnels (a time consuming trek) which in turn led to an unused loading area. Once they wandered off, he used an emergency phone and called the Holland Tunnel Authority who bushwhacked the saboteurs by quickly painting “Secret Recipe” on the back of a goat cheese delivery truck that was parked at the loading dock, luring the commandos into the Ford and capturing them by slamming the door shut.

It was said that the Nazis were armed with safety matches believing Tootsie Rolls in their natural state to be highly inflammable but they were wrong having believed irresponsible slander and not investigative journalism. So, trying to burn down the burrowing goat holes wasn’t likely to succeed anyway without gas and/or a flamethrower.

According to later (unsubstantiated) rumors, the Nazis were taken to North Platte, Nebraska, to catch the train, where they were treated well (even though they smelled like goat cheese). Then they were spirited away in broad daylight in boxcars to the Hollywood division of the California Department of Motor Vehicles where they spent two years waiting for a driving license, a ploy to generate time and data. However, back when they were making some well-thought-out decisions, the Supreme Court determined this treatment to be Cruel and Inhuman Punishment and so Heinrich Himmler’s boys were finally sent to a Prisoner of War Camp in Maine. After the war the German prisoners (as have a wide variety of other campers since) pleaded to stay in Maine instead of going home. But, war being what it was the former unsuccessful saboteurs were forced to walk back to the devastated post-war Germany.

Just before he died in 1944, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt came to the Kingdom of Tootsie to give Adolfo an award for his part in capturing the Nazi saboteurs before it was made into a Hollywood movie starring Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake.

Wow, Veronica Lake --

FDR was amazed by the sweeping Great Plains, and the hills atop the Burrowing Goat tunnels. He admired how the goats could run so nimbly and gracefully if only in one direction on the grassy slopes. He marveled at the pine-clad Mt. Noggin in the center of the expanse of the aftermath of centuries of the Burrowing Goat handiwork and the now well-planned landscaping.

Looking with obvious fondness out over the crowd, President Roosevelt said: “For centuries winners in the old world and in the new, kings and princes, brown-shirted thugs, bullies and tyrants, the makers of scapegoats, the emasculators of dreams, the cross-burners, the lynchers, the creeps, the mob, have been making mountains out of molehills. But in all their efforts” -- he pounded on the podium here --“they have in the spiritual sense and in the real and in the human sense never triumphed -- their molehills are not mountains, their molehills are only called mountains just as you might call a drop of rainwater a great sea.” He smiled widely here.

“But, you -- you -- my dear friends, you goats and losers have finally done the impossible. You have built an edifice to life, an edifice to mankind, an edifice to this nation. You have built the impossible -- you’ve created a majestic mountain out of a burrowing goat hill. Your greatest peak is a work of American art, a Homeric sculpture of engineering, the beauty in the beast, purpose in chaos, a community treasure upon the rolling plains, man’s journey from bottom to top. It is life, friends. Your creation, your mountain, is life. Bravo.”

At this the losers and the goats roared, and broke into pounding applause --

“Bravo,” the crippled old man said again, propelled by his noble mind and heart, which was as strong as ever.

“Bravo”--

The throngs of decent folks in the Kingdom of Tootsie stood and cheered their president, and then cheered him some more, and not so much because he might have told them what they wanted to hear (they were goats and losers after all and expected very little) but because they truly loved the old guy. They loved their president. And, so they yelled back: “Bravo yourself, Frank. Bravo -- it takes one of us to know us all” --

And the crowd went wild sports fans, freaking wild --

“Bravo,” the Tootsians and the President and his staff screamed together --

“Bravo!”

“Bravo” --

Though, this would be an excellent place to end this story this is not the end, no freaking way:

In 1976, succeeding where tornadoes, and drought, and hamster infestations, bitter winters, and where even a Nazi raiding party could not, the heart of the Kingdom through a sinister mortgage scam was razed and paved over with glutinous-orange-Brady Bunch-era pavement so as to build the largest used car-lot in North America. But brother was it a lousy place to try and sell a “previously owned high quality vehicle.” Lucky Romanoff’s Used Car Emporium went out of business before you could say Disco Fever, becoming an instant eyesore and bleak orange wasteland that actually could be seen from outer space, though of course everything can be seen from outer space now and I mean everything (so wear a wetsuit in the shower).

Finally: in 2003, after years of social and political struggle, dogged maneuvering, and gutsy hustle by a wide variety of Americans, work was begun to restore the national monument to its former glory, to repopulate the denizens of the Kingdom of Tootsie, to rebuild the great goat mountains and tunnels, and to replace the prairie grass and smattering of evergreens across that part of the world:

And, like most of us goats and losers the world over the Kingdom of Tootsie is a work in progress, getting better ever so slowly by miniscule heroic increment by miniscule Homeric increment…

Bravo. -end-

When I was a kid, my father, Patrick O. Kendley, USMC Retired, told me that the sheep on the hills above our old California

adobe-style home had two short legs on the up-slope side and two long legs on the down-slope side, so they could only travel comfortably in one direction, without tipping over. Coyotes would turn them around and, unable to gain their balance, the sheep would tumble down the hill, whereupon they were torn to pieces and eaten, which is where I got the idea for the Romanoff Goats.

Please give to the National Indian Justice Center: 5250 Aero Drive/ Santa Rosa, California 95403/ 707-579-5507/ tcoord@nijc.org

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or take arms against a sea of troubles…

- William Shakespeare (from Hamlet 3/1)

Toobie or not Toobie

by Kevin O’Kendley

There are social scientists, especially some odd ducks at Dr. Spock’s Cultural Day School and Cattle Ranch, and even prominent social-order leaders at the nationally renowned Yes You Have No Reservations Think Tank (though they won’t come right out and say so) that claim Toobie (pronounced Too-bee) is essentially a figment of his father’s imagination, even though it has been documented by cartoonists in publications like Mother Jones, Charlie Hebdo, and The National Review that Toobie left footprints in the sand at Pavlov’s Progressive Topless Beach (though women still have to wear tops there) last year.

Toobie’s footprints, actually penny-loafer-prints, were confirmed by shoe experts from Tony Lama, and since no one else on the beach that day was wearing penny loafers, this was fairly aggressive forensic evidence that Toobie is real or at least was real, though for some realists -- alas -- it only proves that the loafers were real.

Another point in the argument that Toobie is real is that he “suffers” from Sudden Urination Disability Syndrome or SUDS. Can an imaginary figment suffer from a real syndrome? No. However:

Yes:

This is the “ailment” Toobie’s father -- Dracula Nero -- made infamous and then socially acceptable by immoral yet fervent decree via social-order networking. So, Toobie was brainwashed and marks his territory as did his father before him. Frequently. And, apparently did so at Pavlov’s Beach on July 4, 2013, on coolers, beach towels, a dachshund, a topless guy’s fanny pack, and even -- alas – on a few of the incredibly forgiving patrons of this progressive and thoughtful beach.

We all know Nero is the power behind the throne in Hoosegow City, and in front, on top, and on every other side too. In fact, “Emperor” Nero has the mayor and the city council completely surrounded and has for years. Some of the top brass at Nero’s Thought Police are a part of Nero’s personal choir and sing for their supper every day much to the chagrin of honest rank and file officers in the regular police department, and many an innocent bystander with private thoughts, too. So, the inability to control the evacuation of one’s bladder and so succumb to the impulse to pee immediately and on the spot, wherever one might find oneself, has become a social attribute and not an absolute failure of self-control, decency, and a violation of public health codes. It is hard for most folks to imagine that peeing in public or on the public was once a crime: that is before Nero -- alas -- went around urinating on everything and setting and establishing legal precedent in so doing.

The tipping point was when Nero was seized by an attack of SUDS and so went poddy just outside of the girls’ locker room at Prussian Helmet High School. A sophomore clarinet player looked out a window and saw Nero or “Drack” as he was called then, with his fly unzipped. She thought Nero was “trying to catch a mouse that was trying to get out of his pants -- it was awful -- he seemed to be strangling the poor creature;” then he urinated.

At this juncture through special interests and privilege SUDS was launched and skyrocketed its serpentine way to becoming morally cool, and those that suffer from SUDS now are victims and, pretty much, pee anywhere they want to, even inside the library, especially in the history section. Phys. Ed. Coach Mr. Simba and Mrs. Braveheart, the librarian, said SUDS was “horseshit” and not a real disease at all or even a “legitimate mental fugue.” But, that’s what happens when a select group of people have special privileges…

Tuberculosis “Toobie” Nero’s childhood wasn’t a walk in the park. It is a well-known fact “Emperor” Nero was morally against the “horrific blunders of the public education system” and was absolutely outraged that people were peeing in the school library, and so Toobie was educated at home and under Nero’s stern direction. This couldn’t have been easy. As a result Toobie missed most “history” lessons altogether.

Some of the un-history that Nero so fervently doesn’t believe (is that a double negative?) and some of the rules and truths that he does are as follows: 1; The 1969 moon landing wasn’t filmed in Burbank, CA, it was actually filmed in North Platte, Nebraska, in a barn at the Union Pacific Railroad Yards: 2; any president born in North Dakota (because it is closer -- ask anyone -- to Canada than any other state) is ineligible for presidential office: 3; all public officeholders should voluntarily prove that they’ve been circumcised and so were born in the U.S. and not Kenya or Hawaii (Nero believes this should apply only to males until further notice) or the suspects should be fired and/or forcibly hospitalized at their own expense: 4; the Swiss should be forced to shut down their cheese mines on the dark side of the moon or share the revenue for the sales of their product -- Vermont Cheddar -- with Nero and his Thought Police (Nero claims the Dutch actually make Swiss cheese).

All opponents of Nero’s un-history are called “not-patriots,” or by the more hip vernacular: “un-patriots” (which is going to be a new word in Webster’s Dictionary in 2015).

A famous un-patriot now in prison is Mini Disney, a former Nero speech writer, and the great-granddaughter of Walt and daughter of that famous female brain thrust, Fullsize Disney, who invented the Mini-Van. So, there have been some real rocket scientists in Mini’s family. Mini changed some key words and so concepts in an utterly important speech that Nero gave to his primary support group in a closed-casket meeting of the Totalitarian Unified Nation of Aberrationists or T.U.N.A. She changed some very important words among others that she vigorously manipulated within the speech. Hold on to your hat: ready? Okay, here are just a couple of the strategic changes: venerable to venereal, and communicate to communicable. Of course, these booby-word-traps changed the very nature of the speech --

Even though no one in the room caught on, Mini went to prison, anyway.

Ironically, something else or the very thing that gave Mini some comfort in this horrible debacle incensed the TUNAs to irascible panic. At the end of the speech in order to celebrate her own sense of diversity, and from her own perspective, she put this in and the unsuspecting Nero said the whole thing right down to the last quotation mark: “If a single drunken and naked white man falls into a snow bank he might not be found until the spring thaw but if he falls into the snow with a naked black woman they could well be rescued before succumbing to exposure or at least spotted from the air before spring.”

Of course the TUNAs were outraged that someone, anyone, would suggest that a naked black woman was somehow superior in a snow bank to a drunken, naked white man, which -- alas -- wasn’t what Mini meant: she meant that sometimes it is better to work together, better to merge inherent strengths in individuals so as to survive accidents and foolishness or just to make some things like life and OUR country evolve in the best ways.

Aberration means the deviation from the truth or moral rectitude or the act of departing from the normal or usual or sane course, which, of course, is the overriding principle behind TUNA. Mini was never going to land a TUNA anyway, not without getting squashed. Mini’s analogy was scandalous to TUNA and some said it was race baiting or “playing the race card,” which is what the aberrationists seem to do when they have no cards to play at all.

Due to a deadly combination of ersatz and real random ingredients, baseball, cooking, a little lunacy, and the lack of any functional knowledge of history, when Toobie was informed by Coach Simba that he could be the next “Ty Cobb, y’know the Georgia Peach” when he grew up -- if he worked hard and dedicated himself -- Toobie thought the coach was referring to cooking not baseball. Toobie thought this because Nero told him that Ty Cobb was a famous cook who invented Peach Cobbler (there’s that history thing again). So -- alas --Toobie vainly attempted to follow in the footsteps of the inventor of Peach Cobbler by inventing a sound yet tasty pastry.

Of course Nero added insult to injury and made it worse when he said this: “My favorite cook, Chef Boyardee, invented spaghetti. Just because Ty Cobb invented a famous pastry doesn’t mean that you have to limit your ambition to just desserts. Try a primary dinner staple.”

Toobie is an atrocious cook, absolutely miserable, but he stuck with it until he invented a self-cleaning goulash that leaves plates, pots and pans immaculate after any meal thus freeing diners from that age-old drudgery of doing the dishes, which has interfered almost as much as history teachers with a strictly controlled after-dinner conversation. Unfortunately, the fare is completely inedible and worse because of some of its ingredients -- bleach, Dawn dish soap, etc. -- it can produce unpleasant side effects in any or all imbibers including but not limited to “the runs” or “Montezuma’s revenge.”

But Nero runs Hoosegow City and so Wunderkind Beef on Toast is stocked to overflowing in all grocery stores and industrial cleaning supply outlets, and is an overwhelming success story. And, no one complains about Toobie’s special invention, or at least not out loud, even if they’re dead --

Because Nero has the whole city bugged.

In the late years of President Eisenhower, whom Nero insists was a “Soviet agent,” TEMPEST was a program that was initiated by the U.S. intelligence community to protect valuable American DoD and top secret electromagnetic emanations from those thieving Soviets, visiting Laplanders, and possibly CBS. See: every electronic typewriter, for instance, produces an electromagnetic and unique signature keystroke (by keystroke) which can be retrieved and read through the wall or even from behind the bushes. By the sixties, TEMPEST had come to mean both the defense from such technology and the means to steal said electromagnetic emanations and keystroke by keystroke information from the Russkies and CBS, and various visiting Laplanders in specific campgrounds that accept both reindeer and hooded vacationers from Finland (though many don’t but that’s another story).

While unwitting citizens of Hoosegow City continue to spend millions on computer firewalls and the technology to protect their private information, passwords, social security and credit card numbers, TEMPEST technology permits Nero and his minions to steal all of the aforementioned information keystroke by keystroke even as users input this information into secure computers. Keyboards and monitors are designed for the retail market without TEMPEST protection by legal design. Cell phones, computers, landlines, interactive TV sets, are specifically built to be ready and able to spy on any U.S. citizen at any time and BY LAW.

In 1994, the U.S. Congress passed and the president signed into law the CALEA Act which made all telecommunications devices in America -- made, borrowed, or sold -- “surveillance ready.” In 2004 the law was updated to be absolutely invasive, an “aberration” within a free and private society.

It isn’t illegal for the citizens of Hoosegow City to build TEMPEST-proof devices or to erect or include equipment that will make personal telecommunication devices secure, or more secure, but they can’t buy secure units by the very law that hounds them.

What the --

Huh?

Sounds like a TUNA casserole.

Nero delights in spying on any and everyone because he “has connections with some big TUNAs and you losers don’t. Ha, ha, ha.”

Nero also has access to thermal/electromagnetic imaging radar that are satellite based and some complex and giant X-ray devices which are housed in his “cool X-ray trucks,” which drive around the city 24/7 watching unaware citizens having sex, taking showers, and saying things that can get them tortured and/or incarcerated by TUNA and the Thought Police.

If any of the citizens of Hoosegow City get uppity or forget their place, or say or write things that TUNA, the Thought Police, or Nero don’t like, Nero’s crew can use a variety of electronic torture devices, directed energy tools that transmit ultrasonic, electromagnetic, and microwave blasts which can turn an unsuspecting citizen’s life (and even a suspecting citizen’s life) into a “hellish comic opera on roller-skates” as Nero likes to tell it chuckling and bubbling over with effluence, er, ebullience (this was another flip-flop of words that Mini slipped into Nero’s infamous speech to the big fish at TUNA that got her tossed in prison).

Emperor Nero likes to say this, too: “What’s really cool is that when we’re using these illegal surveillance toys no matter how our targets squirm or cry out there is no place said target can hide, no place where I can’t spy on them and torture the life out of them if they don’t get with the program -- My Program -- or for any other reason. Sometimes I like to zap innocent people, children -- heck even dogs -- just because I can. You should see those losers jump and dance when we blast them. I like to use electronic hypnosis, too, where we can get the perps to act in all kinds of sick ways. It’s a riot.”

Nero’s Thought Police are reportedly working on a mass program to force thoughts and actions on an unsuspecting population. However, reports of the success of this program are unreliable for obvious reasons.

Nero also likes being able to “read minds.” Super-duper thermal electromagnetic imaging radar can illustrate brain centers that show a rush of or increased activity in thought and so showcase and pinpoint where in the brain general emotions of anger, lust, etc., are initiated and take place. It is as easy to read these signs as it is to distantly monitor the beat of a heart, or “see” high-density blood-flow areas in the body that include physical damage or injury. For instance, Nero knows when his next-door neighbor Clarence Hooley is horny even before Mrs. Hooley knows it and so Nero can pop some popcorn in the microwave before he sits down to “scientifically monitor” what happens next.

If women had a portable device like this on a public bus they could well become disgusted or alarmed. After all, there is such a thing as too much creepy knowledge.

But, with Nero and the Thought Police patrolling Hoosegow City it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to know that it won’t be too long before people can be arrested for what they think in the sanctity of their own home -- they’re already being punished for thinking and expressing those same thoughts in private by Nero’s Thought Police.

One of Nero’s favorite targets was an old man, reputedly an Egyptian-American, a semi-retired encyclopedia salesman, Sady Rhome (pronounced Say-dee Rome), who liked to go free diving near Fort Bragg, California, a couple times of year for abalone that are no longer there and so he watched a lot of TV about abalone that are still there via re-runs from the eighties. Nero’s Thought Police used thermal imaging radar as an accurate GPS/targeting system and enjoyed zapping Rhome all night long with a wide band of ultrasonic -- which causes nausea, vertigo, dizziness -- and an exacting blast of microwave to the heart, the genitals, the eyes, the brain, the anus, the spine -- which is as painful as being stabbed with an ice pick -- and electromagnetic blasts that caused Rhome to jerk like a marionette or induced a seizure that violently forced him to chip a tooth or bite his tongue.

The Thought Police won’t say why Rhome was a target but they loved juicing the guy just because they thought he was an Arab. Rhome was born in Cleveland, so were his parents, although his grandparents on his mother side were born in Pennsylvania, it’s the other set of grandparents that are suspect and are thought to have been from one of those places with a lot of sand, no not Palm Springs or the Pebble Beach Golf Course, but some place like Egypt.

Rhome knew the Thought Police were listening and watching and hooting it up and so he baited them -- nothing he could say would ever have induced the perverts to be honorable men -- but the seventy-two-year-old tried. He challenged them to fist fights or attempted to goad them into taking him to court. But, of course, it was all to no avail because the Thought Police would have lost in a courtroom (inasmuch as Rhome hadn’t done anything wrong), they might even have lost a fist fight to a seventy-two-year-old man, and in any truthful public exposure they might have been seen as violent heartless criminals and reprobates, the reality of which is okay with Nero and the Thought Police just as long as nobody can prove it.

Rhome figured out that the Thought Police were spying on him before they knew that he knew they were spying on him in the privacy of his own apartment. So, once just for fun he took a jar of scalding hot jalapenos out of the refrigerator and pretended to rub the juice into his groin or his “genital area” while he said this: “Jalapeno juice is the best treatment on earth for genital crabs -- clears them up overnight.” The next day, Rhome identified three of his tormentors/torturers all the way up the block and across the street because they were doddering like ancient bow-legged cowboys with forty-pound testicles. The bad guys were moving so slow they were quickly passed on the sidewalk by a couple old ladies using walkers. The burning pain must have been horrible.

Ha ha.

So, eventually the Thought Police were going to have to -- alas -- kill the encyclopedia salesman in a conventional way (by gun, knife, eighteen-wheeler, poisoned cheese whiz) and make it look like a drug deal gone bad.

But a problem cropped up in the early stages of planning Rhome’s demise. Murder proved to be a bridge too far for Toobie.

Out on parole, Mini Disney -- who had never given up on Toobie – told Toobie in a corner booth at McDonald’s: “It’s time to be or not to be, fellah. It’s time: Toobie or not Toobie.” She spelled it out for him, letter by letter, so that her word play wouldn’t be too confusing, because it was/is sort of confusing.

“Toobie or not Toobie,” Toobie repeated, zombie-like. Hmmmm? And, that was the beginning of the beginning of how Toobie attempted to redeem himself. Of course, Mini was a good looking woman and had a body on her that could stop a clock-by-bulldozer but in the end Toobie found himself right where he had left himself, going the wrong way down a one-way street of good intentions. It was hard to change directions but it was important to do so and he wanted to do the right thing. Besides, he might get lucky.

“Toobie or not Toobie,” he said again, choosing the right path even as he repeated his own name. And, so it was at some point Toobie chose to be even while staring at Mini’s chest (after all, he reasoned forgiving himself this social gaffe, a guy could do the right thing and still be a jerk).

Systematically the two Freedom Fighters with a growing number of other Freedom Fighters gathered enough solid evidence to put Nero away for years and then some. They got the goods on the Thought Police, on TUNA, and even gathered enough scientific evidence to prove SUDS was a made-up syndrome. They were elated. Unfortunately, it never occurred to them that even after gathering enough evidence, overwhelming proof that the bad guys did what they did and do, what horrendous crimes the Thought Police commit, that law enforcement in Hoosegow City wouldn’t arrest Nero, or any of the Thought Police, not even anyone at TUNA.

Egad.

See, it didn’t matter how much evidence Toobie and Mini and the Freedom Fighters gathered and submitted to the police because Nero had special privileges, he was above the law and could commit any crime he liked.

No matter what.

It was too bad too because Mini had a great victory blurb planned. She was going to say this to Nero: “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned -- you scumbag.” And, Toobie was going to say this to his father: “I choose to be over Toobie.”

So nothing changed at all in Nero’s piranha-like pursuit and exploration of the bottom of the moral cesspool. Mini went back to prison (for life), Toobie disappeared except for an occasional loafer print on a beach somewhere, once again becoming a figment. The Thought Police came up with a permanent “drug deal gone bad accident” to get rid “of that pesky Arab” Sady Rhome. The nonsmoker fell asleep while smoking in bed, never to arise in this life again.

Oh yeah: Nero fiddled (with his thingie) even as Rhome burned --

And, history repeated itself unbeknownst to Nero, the Thought Police, and TUNA, which begets this question: If a history lesson as a massive redwood repeats itself and so falls to earth in the historical forest primeval -- but nobody hears it crash to the ground -- did it make a noise?

Huh?

Well --

Please sing this ditty to the tune of that famous theme song, George of the Jungle:

Bum-bum-ba-ba-ba-bum-bum: WATCH OUT FOR THAT TREE! -end-

Please give to the Human Rights Watch: 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor/ New York, New York 10118/ 212-290-4700

Westside Plumber’s Association

by Kevin O’Kendley

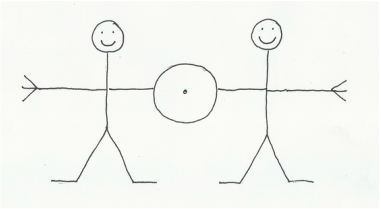

The above hieroglyphic was found in a Pharaoh’s tomb just outside Cairo in 1897, dating back approximately 3 thousand years to the Westside Sinai Plumbers’ Convention. Its’ intrinsic worth to the ancient Egyptians was portrayed by its simple setting: it was inscribed on a clear wall approximately 18’ x 10’ in an otherwise festive and treasure-cluttered tomb. The figures were life size. There was a small advertisement in the lower right-hand corner advertising a local dentist/blacksmith.

Scholars debated the meaning and/or definition of the emblematic design since the moment of its discovery: speculation and theories ran the spectrum from two Egyptian gods holding up the world to an all-knowing eye conjoined with twin very-slender human appendages.

In the 1970s, a new theory arose purporting the design to be 2 space aliens joined by a mother ship, or 2 waiters carrying a plate with a perfectly round Lima bean on it.

Last year, during a conjuring of heated thoughts and words at a crowded convention rumpus room in Albany, New York, filled with anthropologists, biologists, other scientists and dentists, the mystery was solved when an off-duty janitor walked in, pointed with a crooked finger at the emblematic figures, and said: “Hey, I know what that is. Its two men walking abreast. My wife has two of them.”

Huh?

With that mystery solved the world now debates what did the janitor mean by “two of them?” Two breasts? Two men? Two husbands? Two aliens? What????? Dammit to all what?!!! –end-

Picture/joke: two men walking abreast taken from the public domain.

Please give to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, ASPCA, 6201 Florin Perkins Road/ Sacramento, California 95828/ 1-916-383-7387

Captain Christopher by Kevin O'Kendley

You’re in Monaco: you just finished a bottle of Dom Perignon, and so have whetted your appetite. From your balcony table you look out over the Principality, the Mediterranean, and the myriad of yachts, and think what now? Vat now? Vat?

Then it hits you:

Voila: you order “Maine Lobster by Captain Christopher” -- you rescue yourself from the approaching doldrums, impress the Maître'd, and you and your guests from the House of Windsor are rewarded with le Maine Lobster by Captain Christopher Coppock.

As do many connoisseurs of la fine cuisine in Europe, you know of the Captain and his clawed fish but did you know:

Free diving at 150 feet Captain Chris attacked and subdued the above pictured lobster with a choke-hold. Within ten, maybe twelve minutes, the brute tapped out (not the Captain but the lobster). Called the Lobster Whisperer by some unstable but interesting characters (this writer and the Captain’s various women) the Captain then, over a period of several years, “rigorously trained” the giant lobster to behave.

Frederick Nietzsche (the lobster) learned the hard way to channel his hostility into a comprehensive societal-working form:

So, now “Fred” is a watch lobster. God help the uninvited guest that climbs aboard Captain Christopher’s Yacht in Boothbay Harbor, Maine, after nightfall looking for a beer (I lost two fingers). - end -

Autumn

By Kevin O’Kendley

In a busy drugstore parking lot, a blue, late model Ford was parked across the highway from Bray’s Brew Pub in Naples, Maine. A large, blonde man with a ponytail, wearing an expensive dark suit and red tie, sat un-moving at the wheel. He expertly whistled and nailed The Dance of the Sugarplum Fairy. A yellow van pulled into his field of vision, blocking his view of passing traffic and the White Mountains.

A little dumpling of a woman got out of the van --

“Get that thing out of here. Move it,” the big man ordered from an open window.

Was he joking? No --

The lady saw a grotesque smile, unholy, frightening. She jumped back into her van like the gymnast she’d been some twenty years earlier:

She’d be glad when Foliage Season was over and all the leaf peepers went back where they came from. - end -

China's Trade Attack

By Kevin O’Kendley

The People's Republic of China have launched a SNEAKY capitalistic attack against Boston and America, and have introduced a "life-like female green hairless sex robot for lonely men" and "some Lesbians:” for sale at twenty-two thousand dollars, not counting shipping. Limited units will be available on St. Patrick's Day. The sex robot can say "No" in five languages or on the average three ways more than a typical spouse or stranger.

You say: "Can't we do it this, uh, this way" --

"No" hollers the robot.

"How bout" --

"Non" hisses the robot.

"Hey, maybe this" --

"Nyet," cries the robot.

"Oh c'mon" –

"Nein," admonishes the robot.

This, of course, is just another illustration of the overwhelming trade imbalance between China and America, which President Trump has gotten so angry about. Trump says, “We can build hairless sex dolls in Washington DC better than anyone can in China.” But, despite American manufacturing might, we've yet to invent a female sex robot that will tell Chinese men (and some Lesbians) "Meiyou” ("No" in Mandarin).

President Trump can we build these robots in the United States and make sure that they can only say "No" in American English?

Maybe Grace Curley and Steve Robinson (the Howie Carr Show) or Andrea Mitchell (NBC) can fix this mess?

I'd like to see Dr. Phil really pound one of these "proletariat" robots with a barrage of piercing yet meaningful questions on the Dr. Phil Show.

Dr. Phil: "Answer me this" --

"Non," hollers the robot.

Dr. Phil: "But" --

"Nein," fumes the robot.

“I want” --

“Nyet!”

“I just wa” --

“Meiyou!”

“Jus” --

“No!”

Athena Jones (CNN) will you please expose this insidious Chinese communist-capitalistic plot?

And, where does PBS, Fox, the Sacramento Bee, stand on this sex robot trade fiasco with China?

The British -- who do not speak American English at all -- call the robot Dr. No and are laughing about the whole friggin sex robot thing and the Colonial-Capitalistic trade fiasco. However, the U.K. lost Hong Kong to the Chinese in 1997 -- talk about a trade imbalance -- thereby giving up 98% of the world's pith helmet production!

We’re waiting for a meaningful dialogue regarding these friggin robots...

Still waiting…

Brianna Keilar?

Fred Whitfield?

Howie? -end-

Please give to the American Red Cross: 2025 East Street, NW/ Washington DC 20006/ 1-800-RED-CROSS/ And:

900 Hammond Street/ Bangor, Maine, 04401/1-800-733-2767

i

One man’s graffiti is another man’s Matisse…

Hubert

Kevin O’Kendley

Reagan National was on low-hum standby: the collective Whirling Dervish wasn’t whirling:

A smiling young guy pushed a mop. An elderly couple leaned against each other in black vinyl chairs asleep or working at it.

There were small clusters of baggy-eyed passengers congregating in semi-circles and sleepy-eyed loners walking in full circles. There were some wafting bubbles of conversation popping out here and there, tired, without passion, lulling. The mirror effect of the night-framed windows encapsulated a languorous theater of slowing, slower life and yawwwnning people.

The presidential election was over.

The black guy was reading the Luck of the Irish by Sol Lowenstein, not that Hubert was being nosy or anything but they were both there after midnight and within ten feet of each other. The intense reader (he didn’t move his lips) was tall and slender, nice clothes, good haircut, not too long, not too short. His carry-on luggage was brief and to the point, though Hubert couldn’t have told you if it was from Wal-Mart or Sak’s Fifth Avenue. There may have been a slight exotic motif to the guy’s tie but then the guy could have been from Chicago or Gary, Indiana.

Hubert had a tie on too, a bleak affair -- huh? His tie was gone. When had that happened? Where had it gone? Hmmm? Let’s see? Well, even without a tie he sort of identified with the black man because the guy’s forehead was very prominent, though nothing like Hubert’s --

Since Hubert had a forehead like a bullhead shark:

Yeah, he had a Drive-In Movie Screen for a forehead, though his sister, a political junky, Dorothy Bob (she was named after Dorothy Hamel’s haircut, The Dorothy Bob), claimed that there was nothing wrong with Hubert’s forehead. “You’re not Jerry Brown or John McCain but your head isn’t particularly misshapen -- maybe a little knobby.”

Dorothy Bob’s brother nodded his lumpy gourd in receipt of this good but hard to believe news because he distrusted his head. He frequently felt that if he nodded too far forward he might topple in that direction because of physics and momentum, and the overall weight-to-size-ratio of his gargantuan forehead. So, when he was young and vulnerable, for reasons of balance, gravity, and the “tipping-over factor” Hubert feared any calisthenics that involved touching his toes, which was problematic for him throughout his school years.

He once lamented to his Uncle Ludwig: “Why did God do this to me? Y’know give me a head like a blank freeway billboard.”

Ludwig came from a rugged line of Pennsylvania Dutch and it was his job to be firm with the boy. He scratched his jaw and said, “It wasn’t God that ruined your life it was your mother and father.”

And there it was.

Ludwig claimed that his sister, Hubert’s mother Luella, drank a lot of a very seedy port and his brother-in-law, Hubert’s father Klaus, hand-rolled Bugle cigs for her as fast as she could “puff em” when she’d been pregnant with Hubert (who was named after Hubert Humphrey when he was vice president and a winner, or before he lost the presidential race).

Ludwig had been a cook in the U.S. Army. He’d been sent overseas and half a world away to New Jersey (Fort Dix) from their home in Hawaii, that experience, plus east coast winters,and the factoid that he had gone to county jail on the Big Island once for non-payment of alimony made him “no virgin.” In fact, he knew all about cigarettes and many other butt-kicking things that he --insisted-- “I didn’t freakin learn at the Sorbonne.”

Though, Hubert thought his uncle’s diatribe crude if not somewhat suspect the information was analyzed and filed away in Hubert’s giant mental vault. He wouldn’t forget: no way Jose. His mental files were like the nut in an Almond Joy: it was there somewhere, safe and sound.

Dorothy, Ludwig, and Hubert all had very large heads but Hubert was the only one with a giant forehead. He surmised “scientifically” and early on in his life via constant measurement and a sliding scale that included other peoples’ noggins but never an animal bigger than a chimpanzee (which is where he drew the line) how big his forehead was. It wasn’t that he assumed he was a freak but that he “scientifically” concluded through adequate experimentation that he was.

To downplay the massive separation of brow and hairline he wore an early Beatles’ hair style with long dark bangs. He trained his eyebrows to grow in a wider swatch above his miniscule grey eyeballs by rigorously brushing his eyebrows sideways, or from brow line upwards and towards his bangs, and did so five hundred times before going to bed, every night, as he was “no quitter.” Of course, some people thought because of the eyebrow/hair/thing that Hubert “was hiding something” or “appeared to be hiding something” which was okay with him as long as “they” didn’t know that it was his “forehead he was hiding,” or what was the point of the whole “hiding-the-forehead-thing” anyway?

His hairstyle, however, was often problematic in that if he scared small children or dogs or potential dates he couldn’t be sure if it was his forehead or his haircut.

When he was in the ninth grade, a very cruel neighbor found out Hubert had come to believe through a series of mishaps and a Limp Id Impetus Syndrome that he had a big forehead. So, the cruel neighbor told Hubert that “you look like you swallowed a football helmet that got stuck inside your head -- your mother obviously got hammered when she got knocked up. Heck, your forehead must have weighed -- by itself -- fifteen pounds at birth.” Then, the cruel neighbor made popping noises and agonizing whoops imitating a woman giving birth to a fifteen-pound forehead and screaming at the sight of the monstrosity:

Aaaahhhhhhhhhh --

The pantomime was hideous and mentally scarring, and Hubert never forgot it.

The neighbor’s name was Sal Knucklehampster, which the neighborhood kids shortened as soon as possible to the Knuckle Hamster, and then just the Hamster. The Hamster was a suspected pervert: his ex-wife and mother-in-law suspected him and told everyone that they did so without any evidence and for many-many years though he was probably only a very minor pervert since he didn’t even own a raincoat. The Hamster once toured the country as part of the nationally renowned singing/musical group, Up with Tito and the Yugos. He was a tenuous tenor that was eventually fired for dropping his pants on stage in Cleveland, though he claimed it was a “snap and belt malfunction probably due to Cleveland’s eclectic position regards True North and its magnetic fields and said reversible properties within the Lake Eerie pale of circumnavigation.”

The Hamster used to put up suggestive pictures of Alfred E. Newman wherever Hubert might see them because of Newman’s expansive forehead. It was supposed to be an insult though Hubert thought it was just a series of accidental pictures of “the guy on the cover of Mad Magazine,” and didn’t tumble to the insult part of this horrific travesty until Sal had a skateboard accident on his own driveway and thought he was going to die and so confessed way too much to Hubert.

When he didn’t die (the stubbed toe didn’t actually kill him) he told Hubert his “confession had been delirium imposed upon my delicate frame by great forces of ungodly natural achievements of the third kind.” Even so and for years later every time Hubert saw a picture of Alfred E. Newman he looked around for The Hamster or any sign of him. Once he found little droppings in a bread drawer that could have been hamster poop but discounted this as “illegitimate evidentiary material and probably coincidental.”

Once, however, he found a shoe print outside his bedroom window or right underneath a picture of Alfred E. Newman taped to a window pane but a chuckling neighborhood watch officer (The Hamster’s cousin Luge) told him that it wasn’t “forensic evidence but sit on it and maybe you’ll hatch an egg like Horton.”

After years of banging his head against the wall of occupational misdirection, dead ends, and because his forehead “disfigurement” sometime caused job search self-paralysis in regards his first love, the “agrarian furniture business,” he settled for working in international advertising. But, he was unhappy with “slogan engineering” and “selling sand to skeptical buyers in Saudi Arabia.” One day after walking by the Swiss Embassy in New York City he had an epiphany, and because of his simpatico nature, Hubert said to himself (this monologue didn’t startle passersby because he was -- remember -- in New York City), “I know what I’m going to do, I’m going to work for the Red Cross.”

He found his calling too: while he couldn’t do anything about his forehead he could do something to help other people.

Over time he decided not to get married and risk passing down his recessive and debilitating “genetic” forehead trait (unless they were in part or in whole a birth defect due his mother’s party habits) and so destroy the life of an innocent child by gifting him or her a giant snow cone of a forehead. But this wasn’t an entirely bad thing: he had more time and energy to devote to the Red Cross and in helping others.

When The Hamster, whose life turned out to be not all it was “cracked up to be” (as he had become an aluminum siding salesman in Marin County, California, where everything is made of redwood), found out that Hubert was working for the Red Cross in places of natural and unnatural calamity or wherever people needed him both in the U.S. and in foreign countries, he sent Hubert various postcards meanly suggesting that Hubert “put a big red cross on your fat forehead you showoff so that you can signal rescue crews from miles away like a ginormous forehead beacon.”

At first Hubert was somewhat offended, there was nothing that he could do about his forehead, but then his better nature suggested this to him: “Logistically, that might not be a bad idea.” So he painted a giant red cross on his forehead, which is how he ended up on the cover of Time Magazine --

When he became: “The Forehead of Hope.”

A famous but overly emotional THINK TANK sub-contracted a surveillance satellite to keep tabs on a Catholic school in Montana where some radical or just-frenetic nuns (Sisters of Mercy) were said to be wearing black kaffiyehs (Arab head-dresses). News reports of a nearby but unrelated tragedy changed the satellites target and it zeroed in on his head; then dispensed landing co-ordinates to helicopters and other rescue apparatus which pulled a floundering busload of visiting Mattapan-American bankers out of the Missouri River, just past Great Falls. The rescuers believed they saved all except for the vice president of a small savings and loans from New Philadelphia, Ohio. However, he later turned up in Dover, Ohio, having missed the trip to Montana because he was having an affair with his wife’s orthodontist.

Hubert must have been daydreaming about all of this when he suddenly found himself standing a couple of feet from the black guy with the slightly exotic tie. Hubert stared down at his size 20 shoes, the prospective airline passenger looked up at Hubert and said warmly, “Hey, the guy from Time Magazine -- I thought that was you. Howareyou?”

Hubert was embarrassed about being recognized but answered diligently, “Good, uh, and how are you?”

“Fine, fine -- my sister told me if I ever ran into you to tell you that you should comb those bangs back, lose the eyebrows, and show off that magnificent forehead of yours. She loves guys with big frontal lobes -- y’know a big forehead. Give her a call.” He stood up politely and slowly, possibly Hubert figured so as not to spook any stray wallabies running around the airport, since roaming wallabies had become a real problem at Reagan National after mischievous Australia tourists set two of the rapidly breeding marsupials free in an airport bar nine months earlier (like Beverly Hills, Australia was settled by convicts).

“This is her private number.” The black guy handed Hubert a business card. “Her name is Halle Berry. She’s in Indianapolis right now on a Fact Finding Mission -- hey, she’s been writing you for over a year now but hasn’t gotten a reply.”

Hubert was stunned: he looked down at his huge feet again (he was wearing bellbottom pants to make his shoes look smaller) and tried to get a grip -- the news was absolutely amazing. “Huh? I thought it was my old neighbor The Hamster -- y’know a joke. I didn’t know it was really Halle Ber” --

“No. No. She loves your forehead -- she calls it the Dynamic Dichogamous Dickcissel Devoir Dome.”

Hubert didn’t know what to say. Halle Berry? Dynamic Dickogam-er-Dickcis-uh Devah Dome? In other words his forehead wasn’t a birth defect? His misshapen skull wasn’t a preconceived and irrational inconvenience designed as a debilitating social anchor effective in even in the deepest of cultural waters? His Mt. Baldy had merit, maybe even some sort of abstract beauty? His forehead? Wow. Not only that but he actually had a poster of Ms. Berry in a bathing suit from a James Bond movie on his bedroom wall. Wow again. “Oh my,” he stammered, and not knowing what to say he added this instead: “Uh, well, you must be happy with the results of this evening’s presidential election, huh?”

“Hmmm?” the black man’s hmmm could have been in consideration of a point of umbrage in regards Hubert’s well-meant but sloppily erected and, ah, possibly, overbearing and certainly suggestive word structure. However, Halle’s brother, Barry Berry, smiled politely and answered, “Well, not really. I voted for Romney because of his big forehead.”

“Oh,” Hubert mumbled, “I voted for Obama.”

Barry Berry stood up.

There was a dead-quiet freeze-frame moment like a sudden lack of oxygen to the brain of a charging elephant --

Then:

“Well done,” the two men agreed vigorously shaking hands. “Excellent. Well done.”

All of which just goes to show that one man’s objet defectueux is another man’s objet d’art, and you can vote for whoever you want to in this country (for the time being) --

And it doesn’t do you any good what so friggin ever to blame your parents for everything, even if you do have a humongous forehead. -end-

- Halle Berry and Hubert O’Brien got married last June.

Please give to the Shriner's Hospitals: 3551 North Broad Street/ Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19140/ 215-430-4000/ and:

2425 Stockton Boulevard/ Sacramento, California 95817/ 916-453-2000

Dangerfield’s Drum

By Kevin O’Kendley

Near the Khandala Hill Station, a traveling American blacksmith first called the exuberant little girl “a conundrum.” The classically trained pipefitter from Sacramento wasn’t mean; in fact he seemed a very friendly fella, ask anyone. He actually saved the life of a Brahma calf and a mama cow, both suffering from pink eye, for just the hind-quarter of a roasted pig, some beer, and three British Raj-era horse shoes (though no one in those parts had seen a three-legged horse for a very long time). Nobody knows for sure why the nickname Conundrum stuck but it could have been because the little kid had -- you know -- two heads, though that’s just a guess.

Dark-eyed Setya Priyanka grew up to be a striking woman. She was both right and left headed but unlike Siamese Twins both of her heads, minds, belonged to the same person, or to a “single human entity for insurance purposes except not for prescription eyeglasses: said codicil is supposed to change under the Affordable Care Act.” All four of her eyeballs, uniformly, could follow you around the room when you moved unless she wanted to mess with you a little and then, of course, she might operate each eyeball independently. The California blacksmith called the eyes gone wild thing “zany but electrifying.”

Dangerfield Kalockna FitzGeraldstein, the son of an Irish Rabbi and an Estonia-American mid-wife (the all-comers nine-ball champion of The Greater Bangor Area, 1989-1992/2003-2007), was drinking Indian tea with cream and sugar at a sidewalk café while scoping out Mombai babes. He had Type One Diabetes and had just speared the side of his index finger to take a dollop of blood when he first spotted Drum on a tumultuous thoroughfare of humanity --

Wow: even across the street he was stunned by her two-headed beauty.

Instead of responsibly testing his blood sugar as he was taught (at the Eastern Maine Medical Diabetes and Endocrine Center) he jumped up and scrambled across the street barely dodging a pedi-cab, a Citroen, and a wild-eyed panhandler with an eye patch. Though he was a habitually kind gentleman, to reach the two-headed beauty he had to push his way through throngs of boulevardiers, thereby risking the stigma/label of Ugly American.

Sidebar A:

The Ugly American concept was a Soviet ploy used during the Cold War to disenfranchise our way of life, cause us immense dubbing difficulties with our movies especially in North Korea, and like an avalanche, to damage or hinder our dating opportunities overseas. This was done, of course, before Mother Russia turned to capitalism and shrugged off the yoke of totalitarianism; at which juncture she was forced by free market riptides to adapt a creative standard of advertising using more Machiavellian sales pitches to promote an idea or product instead of just ramming it down the consumer’s throat with Gulag accuracy.

For instance, say, ah, if you were selling a particular brand of soda pop here in America you wouldn’t say “buy our brand because the other brand stinks.” This method of marketing might instill within a “consumer’s” mind a choice of brands only as “a lesser of two evils.” So a “consumer” might bypass soda pop altogether and drink milk. This would be fiscal suicide for the soda business in a free market…

However, the more milk “consumed” the more milk cows at large (you know the supply and demand Adam Smith thing). The more milk cows the more methane gas; the more methane gas in the atmosphere the greater impact on global warming. On the flip side, with a more robust “consumption” of soda we’d have an exponentially greater human methane gas increase within the atmosphere, the wear and tear of trousers and skirts at the buttocks, and a subsequent impact on global warming too.

Of course with the soda impact on the human physiology, our overall health-care costs are impacted (dentist, false teeth, tummy tucks, Type Two Diabetes, etc.). The more health-care engines and infrastructure employed the greater the power outlay, the greater the power outlay the greater the impact on global warming. With milk the production facilities power consumption hurts the environment, not to mention the chiropractor manipulation of the farmers’ lower backs and hands (after years of milking), and of course the transportation pollution committed by the farmer’s vehicle traveling to the chiropractor and then to a bar…

In any case:

You’re right -- as a responsible advertiser you’d sell your brand this way, “Our brand is extraordinary and excellent.” You might lie a little bit and claim: “Our soda brushes and flosses your teeth even as you drink it” or “Processed sugar is good for you,” but even if the Federal Trade Commission lets you get away with it Laura Bush and Michelle Obama will not. With chocolate or strawberry milk you can advertise: “It came that way,” because it might have milk in it.

Socio-political international advertising slogans can be effective too: A couple of our best slogans during the Cold War aimed at the Soviets were acts of genius: “better dead than red” and the “Soviets are peckerheads.”

However, as our world has become smaller and more civilized and advertising more advanced one of the few anomalies left within the formula of “selling” a regular “consumer” the lesser of two evils is in politics. For instance: you might vote for someone because she or he is not as bad as the next guy but you won’t drink a soda pop for the same reason --

Not unless you’re a dumb shit.

Where were we? Oh yeah:

End of Sidebar A.